Black History Month - an Opportunity to (un)Redact the Facts

This article first appeared on Medium.com on February 2, 2023.

Disclaimer: In this article, I mention organizations by name not to shame them, but to serve as examples, learning tools. As a scientist by educational training and lifelong learner whose favorite subject in school was math, I appreciate the benefit of learning from and dissecting examples. Thank you.

Is it the ethical duty of architects, historians, historic preservationists, journalists, communications teams, teachers to (un)redact the facts of historical narratives to tell a fuller history? Something to think about as many professionals prepare to post social media posts and write articles for another Black History Month in the US.

Grammar matters. When it comes to writing about Black History in the US, my history, our US History, for centuries, the way you have written about it has done the most harm to those that need the most care at the center of this historical narrative — Black people. To not only be the recipient of emotional, psychological, and physical abuse for centuries in the US, but to then have the narrative about the abuse not state who murdered us, who abused us, who enslaved us exacerbates the abuse.

It’s a form of gaslighting where the historical narratives have not been ones of accountability. They continue to omit who abused Black people and benefited from the abuse — White people. The choice of redacted grammar and language (RGL) continues to be harmful to me as it makes my pain and my ancestors’ trauma feel invisible. Instead, redacted grammar and language makes White ancestors invisible in the historical narratives that journalists, architects, preservationists, and more write about slavery, lynching, redlining, and more in the passive voice.

It is risky to provide a critique about someone’s writing. And for the subject at hand, I am willing to take the risk. If an organization or individual states on their website or in public that they stand for racial equity, stand for telling the full American story, and they write in the passive voice or speak in the passive voice about slavery, they cannot frame their mouth to say “White people” when talking about White people lynching Black people and instead use euphemisms for White people like the “wealthy elite,” they do not stand for racial equity.

Instead, they are a co-conspirator for white supremacy. The passive voice is the grammar of omission and to uphold white supremacy, co-conspirators erase anything that might associate White people and whiteness with anything bad, like the horrors of history. It creates psychological distance on many levels:

:: between the author and the reader, i.e., a level of objectivity

:: between the person/people (White person/White people) who committed the action verb (enslaved, lynched)

Breathe. Now, let’s continue.

Hi, I am an architect who specializes in historic preservation and managing construction projects on behalf of the building owner or tenant. I am also a Black woman, a writer, an artist, and a business owner. When I was a graduate student in architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I received advice from someone, maybe a professor, that to succeed as an architect, it is important to “know how to write”.

Know how to write. I wonder how many architects and other professionals have received similar advice. During my graduate studies in Champaign, I took a class in professional writing — not in the School of Architecture, but in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning. It was a required course for my other master’s degree in urban planning. A favorite course of mine, one of the many things I remember from that course is that words have the power to shape our perception of the world and of each other. The message: Language and sentence structure, grammar, have power. Specifically, the story we shape from the data we collect as urban planners has power. We can frame a narrative about a community simply by the words we use and how we assemble those words — just like placement of walls and doors on an architectural floor plan. The same applies to architects — the stories we write about the places we design have power and influence over the way we perceive each other.

I return to the abridged version of the advice I received as a graduate student: know how to write. In spite of the education we receive as far back as junior high school, most of us do not receive enough emphasis on the “how” and the ethics behind it. Writing that does not expand on “how”, is void of context and nuance, i.e., the passive voice, omits facts about a place. This omission might serve your client if you are writing a de-nomination form for a potential historic landmark, but it does not serve the community-at-large and their collective memory. The result of writing devoid of “how” of history? Landmark nomination forms in their municipal archives, full of redacted history because of this omission by the author of the nomination form. And, it snowballs because researchers cite the nomination form in the passive language the author used — the redacted history lives on.

My earliest exposure to “know how to write” began in the seventh grade when my English teacher told my classmates and I that we use the passive voice for “professional writing”. As an adult, I now see that the passive voice is a way to evade responsibility, to hide who did what to whom. Although, it might be best to use it in a legal context to, for example, evade libel. Also to use a legal term, the passive voice creates redacted facts about events and places — it does not tell a full story about history. It does not tell a full account of history. And, if we look to truth and reconciliation as a means of healing our country, the passive voice and other redacted grammar and language in historical narratives will not get us there.

If we examine historical narratives about US History, in textbooks, lectures, and more, it is a redacted history that we often read and hear. This circumstance is especially the case of uncomfortable history, often where non-White people experience abuse at the hands of White people, across the spectrum of income, both wealthy and poor. And the students who learn this redacted history and learn to write in the passive voice as “professional writing,” become the professional architects, historians, historic preservation consultants, and journalists who write context statements and historical narratives about buildings and sites.

Beyond Integrity. How I began on this journey of truth telling in historical narratives goes back to 2015 and miles from Champaign, IL, in Seattle, WA. The year 2015 was the year that I began volunteering in an organization, initially its organizer, retired Director of Preservation Services at 4Culture Flo Lentz named, “Equity in Preservation”. By unanimous vote, my co-founders adopted the name I picked, “Beyond Integrity”.

Beyond Integrity in (X) Conference poster (2021)

What inspired Flo to found Beyond Integrity was the Seattle Landmarks Commission’s decision to not nominate for historic landmark designation a Black historic site in Seattle’s Central District, Liberty Bank. The primary reason for the decision was because the nomination form written by the developer’s historic preservation consultant provided a strong enough case against the architectural integrity of the building at the time of the landmark hearing. Liberty Bank lacked enough architectural integrity to be a strong enough contender for Seattle landmark designation. Since then, in part because of research and auditing of past landmark nomination forms that exposed bias in the context statements in the nomination forms, the Seattle Landmarks Commission has made strides to reconcile for past errors in judgment. A lack of architectural integrity, as reported to the Commissioners in the redacted facts of context statements, written by the architect or historic preservation consultant, led to the rulings to not nominate for landmark status.

In this period of my career, I observed first hand how we, architects, historians, and historic preservationists can craft a narrative in support of or against the landmark nomination of a building or site with the data we observe about it. This narrative can harm or support it, fulfilling the architectural integrity criteria of the nomination form in the eyes of the landmark commission. In the case of Liberty Bank, it was my graduate course in professional writing come to life, almost ten years later, in a landmark de-nomination form written by architects and historic preservation consultants, hired by a developer who did not support landmarking because they wanted to demolish the Bank and build in its place affordable housing — a topic for another article.

(un)Redact the Facts. My journey continued in 2020 — I know, 2020 seems like yesterday. The National Trust for Historic Preservation (“NTHP” and “National Trust”) owns nine (9) historic sites and co-stewards 11 historic sites. Like many institutions and corporations, the National Trust made a post for Black Lives Matter in the summer of 2020. Their post addressed graffiti on a building they co-steward, the Decatur House. It was a wake-up call for a national institution. While the post shared how the National Trust “tells the full American story” by highlighting the contributions of African Americans to the United States, in the preservation of buildings related to Black history, their post failed at telling the full story of chattel slavery in the US by using the passive voice to describe what happened in the Decatur House in its early life.

The direct quote from the Instagram post:

“This place, where people were held in bondage within view of the White House, has particular meaning in this time. The National Trust for Historic Preservation and the White House Historical Association honor this by telling the full story of our history, by elevating and preserving the enormous contributions African Americans have made to our nation …”

In a direct message to their Instagram account and then via email to NTHP, I suggested an active voice revision with the direct object, White people, clearly stating who did what to whom in the Decatur House:

“This place, where White people held Black people in bondage …”

By using the passive voice, the National Trust gave a whitewashed or redacted account of the Decatur House’s history. With the use of the active voice, these revisions I provided (un)redacted facts about this landmark that sits across the street from the White House.

Due to my persistence, I received a response from Paul Edmonson, the Executive Director of National Trust, but no revision during the summer of 2020 or by the time of this publication. I sent subsequent (un)redacted revisions to their social media and online publications that told a fuller story about US chattel slavery. They did revise one of the online publications per my (un)redacted revision. But, for a major revision that speaks to their 2018 work with James Madison’s Montpelier on “Inclusive and Equitable Narratives,” they did not cite me or attribute the revision to me. Citing Black women is a part of inclusive and equitable narratives, for it lets us and others know that our voices matter.

As of December 2022, the National Trust continues to state they are Telling the Full American Story while they use the passive voice to describe slavery, describing plantations as places where, “Black people were enslaved”. In 2021, thirty plus people and an international design organization signed on to a Call to Action addressed to the National Trust to change the grammar and language they use in historical narratives about slavery and still no change.

Cover image for the Call to Action and post from @unRedacTheFacts’ Instagram Account (2021)

In May and June 2022, I revisited unredaction on Wikipedia where I unredacted the definition of the word “plantation” in my first Edit-a-thon called, “unRedact-a-thon”. Ironically, an editor redacted my unredactions in the few articles I edited, most notably, the Plantations in the Southern United States article. The editor explained that some might view my edits as being “controversial”. Yes, replacing “plantation” with “forced labor camps, i.e., plantations” might be controversial, but an accurate description of places where White people forced generations of Black people to work, without pay under threat of torturous abuse such as rape and murder.

Given that the preservation of forced labor camps is a prominent fixture in our profession, I encourage, no, demand that you write with empathy for your audience, the audience that matters the most — the victims of the abuse at these places of contention, Black people. unRedact the facts about plantations and use language that clearly describes them as the tortuous places that they were, therefore clearly describing the experiences of the generations of Black people who lived and worked there. Write with empathy for your audience — more on that later.

Screenshot of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice page from MASS Design’s website (Feb. 1, 2023).

In October 2022, I visited the MASS Design website, curious about the firm, I explored a few of the project pages. When I arrived at the page dedicated to their design of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, I noticed that their narrative omitted something, rather the two key groups of people at the focal point of the memorial — lynching. In not one paragraph did I find a mention of “White people”, the perpetrators of over 3,000 lynchings of mostly Black women and Black men, and not one mention of Black people, the recipients of the brutal crimes committed by White people. As people recall or research the tragedy of lynchings, one finds that White people commemorated these brutal murders with postcards. Sometimes, eerily at the forefront of the postcards are White children surrounded by a crown of White men and women.

A sentence from the project narrative: “The community remembrance process allows communities to confront history by becoming active participants in the commemoration of lives unjustly taken.”

In 2019, the Library of Congress (LOC) published a tool for teachers to help them use primary sources from the Library’s collection as a part of their larger blog that premiered in 2011 called “Teaching with the Library of Congress”. In it is a “Teacher’s Guide Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts,” that, in summary, provides guidelines for teachers to encourage students to “Observe-Reflect-Question”. Under the Question column of the worksheet LOC guides teachers to, “ask questions to lead to more observations and reflections”, to think about the following questions when they review LOC materials: “What do you wonder about … who? what? when? where? why? how?”

Viewing the sentence from MASS’ description of the EJI memorial through a lens of critical thinking, I question: Who unjustly took the lives? Whose lives did they take? Why did they take the lives? There is so much missing in language and grammar that waxes poetically about the horror of lynching of Black people, some who were pregnant Black women. We cannot afford to write redacted history that treats White people like invisible players of our history by omitting them in our historical narratives of uncomfortable history related to our design projects.

Returning to the critical thinking about MASS’ historical narrative: The answer to the first question is White people. The answers to the second question were Black people, Chinese people, and Indigenous people. Of the over 4,000 people who White people lynched — the vast majority were Black, a few were White, White people who advocated for Black people to have “equal rights”. So, why, out of the 367 words to describe the memorial, did MASS not include the words, “Black people” or “White people”? MASS is not alone in architects and designers in writing redacted historical narratives. And yet, I am encouraged that we can change because we as designers already engage in a process of “revise and resubmit” called participatory design. With the feedback that I am providing, we can revise the way we write historical narratives and thus practice racial equity.

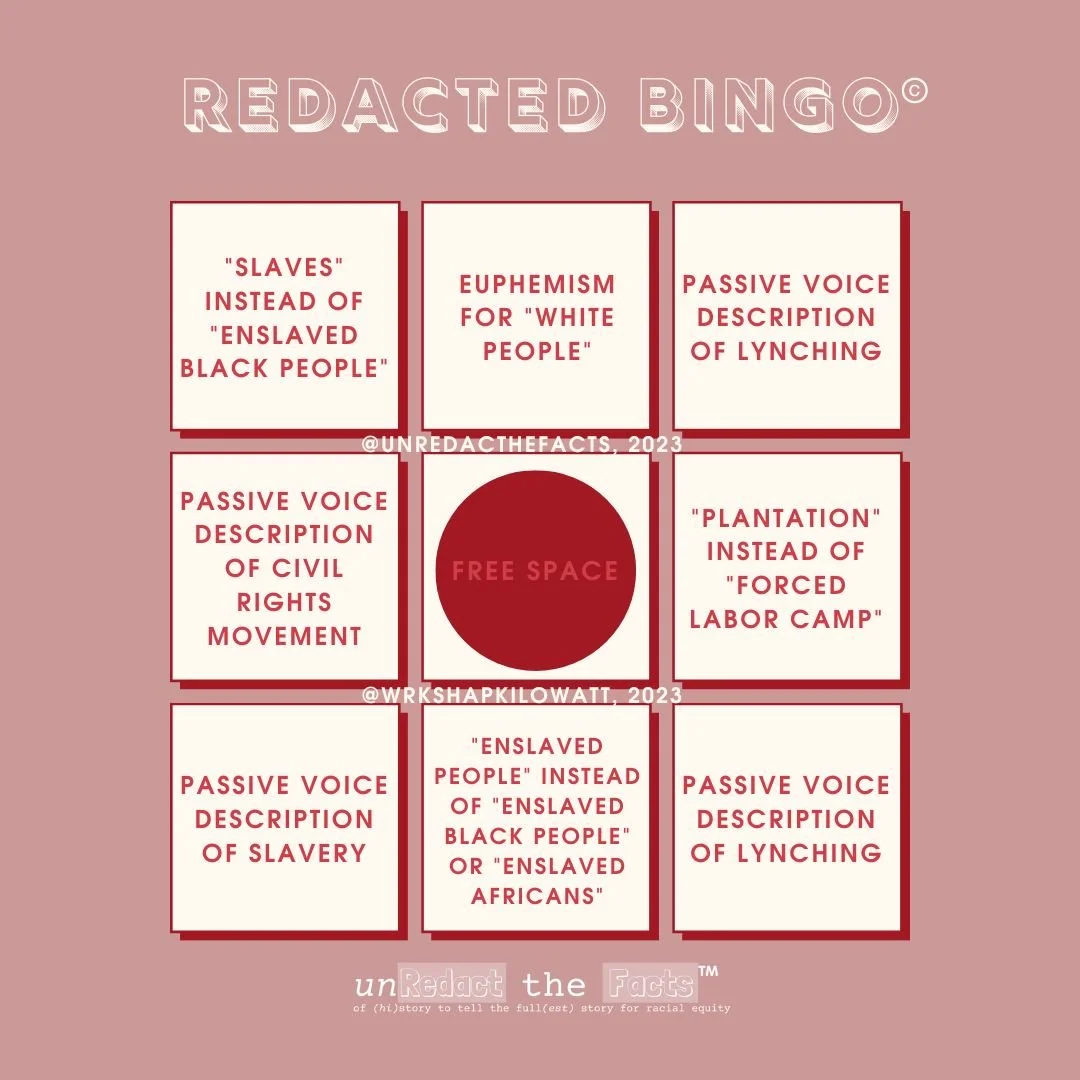

For some educational fun this Black History Month in the name of unRedacting the Facts, consider playing Redacted BINGO! Learn more about the game, register, and view the press release here.

Redacted BINGO card infographic (Jan. 31, 2023)

Empathy for the audience. On November 21, 2022, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) announced on their blog that they updated their equality/equity bicycle visual and how the change came about. After receiving unsolicited feedback on the graphic, RWJF surveyed their newsletter subscribers and implemented the feedback they received from 1,100 respondents. This feedback loop is equity in action, participatory design. It is empathy in action.

From the article, written by RWJF’s Creative Services Officer/Brand Officer, Joan Barlow, the feedback they received on the initial visual, “led to many conversations, and they reinforced our view that our bike visual did not work well for everyone. So we concluded that it might be time to refresh it.”

Tweet from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, announcing the new illustration (Dec. 6, 2022)

I commend RWJF’s awareness and accountability. Joan concludes, “I have always believed that good design advances conversations and makes choices clearer. With our new equality/equity visual, we hope we have done that. I try to approach this, and all design challenges, with empathy for the audience. I think that makes me a better designer. But this one is very personal to me, as I know firsthand the importance of equity and removing barriers.” If a participatory process can occur for revising graphic design, then it can happen for another field of the arts, yes? Perhaps, the art of writing historical narratives in the active voice instead of the passive voice?

I reflect on these questions and I reflect on what Joan said, “empathy for the audience” as I advocate for replacing the passive voice with the active voice in historical narratives about slavery, lynching, i.e., Black History/US History/White History. And, as a Black woman, like Joan, “I know firsthand the importance of equity and removing barriers”.

If we can design with empathy for the audience, then we can write with empathy for the audience. And I would even go so far as specifically stating the audience that needs the most care in the narrative. In the case of historical narratives about slavery, lynching of Black people by White people, etc., writing in the active voice demonstrates empathy for the audience that needs the most care — descendants of enslaved Africans and their ancestors — the past, present, and future. Speaking to my fellow architects, we have a standard of care to uphold. To me, that extends to the written and spoken word.

Empathy for your audience is something to think about as we publish articles in celebration of Black History Month, give talks related to Black History, and host events for what is in essence US History. And, something to think about when you write context statements for your landmark nomination forms for local and state designation. For, everything we publish about the built environment is a part of the collective body of work that someone after us will read and cite.

Again, I ask: As professionals in the preservation of cultural heritage, is it our ethical duty to (un)redact the facts in our historical narratives to tell a fuller history for racial equity? For architects who are members of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), according to the organization’s 2020 Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, perhaps it is. From the Code’s “Canon I”:

E.S. 1.3 Natural and Cultural Heritage: Members should respect and help conserve their natural and cultural heritage while striving to improve the environment and the quality of life within it

Redacted language and grammar (RGL) does not tell the full story about natural and cultural heritage. Instead, it aligns with the goals of white supremacy — to create psychological distance from and dehumanize Black people and their historical experience. The use of RGL is the same as banning books and history courses on African American history, current legal practices in many US states. If your goal for using redacted grammar and language in historical narratives is to be objective, dispassionate, and neutral in tone, then perhaps question why you choose to be any of these things for a painful history that calls for taking a stand for racial equity and democracy.

be kind to yourself and others.

(un)Redact the Facts is an initiative of wrkSHäp | kiloWatt, a boutique architecture firm owned and operated by k. kennedy Whiters, AIA, that specializes in historic preservation, owner’s representation/construction management, and racial equity communications.

k. kennedy Whiters, AIA is an architect with licenses to practice in New York and Washington State, a published writer, an artist, and a business owner. She was a 2008 recipient of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Mildred Colodny Fellowship. In 2021, she founded Black in Historic Preservation, (un)Redact the Facts, and Beyond Integrity in (X). The latter was a national historic preservation conference that focused on the topic of architectural integrity of historic landmarks. She’s been known to hug a tree and a building or two.